My Top Films of 2023

Where I launch this Substack and I go back to making a list, checking it twice

The happiest part of my writing life is whenever I am not doing it for a deadline. Anything becomes a performance at some point, but at least when I write purposelessly (sort of), I tend to be less beholden, more casual. It’s like going for a hike alone. You don’t have to talk to anyone. You focus on the walking. You listen more to the sounds around you.

I know some people who try and watch every awards contender possible before coming up with a list. And I wonder: Why bother? You can’t possibly be in all these places where all these films are shown. The best part of list-making is the limitation, how it reveals where the list-makers are from and what films get shown in their cities and towns, what films get streamed and pirated at a given time.

For instance, my list would tell you that as a Filipino film critic I am useless. I am living outside of the Philippines, and I still have a philistine attitude towards Netflix, where some Filipino films are already available. I’ll do better next time. For now, I remember one of my close friends telling me that Netflix is where films go to die. It’s a cemetery and browsing through its carousel is like reading the inscriptions on tombs. One day I’ll write about that. As fate would have it, my #2 film is on Netflix.

I have the gall to make a list because, as someone fanatical about contemporary cinema, I have seen a quite a few this year. The ambiguity of “Had he not seen it, or had he seen it and didn’t like it much?” is one that I find thrilling. All right, then. Henceforth are the movies I cherish the most from 2023.

1. Close Your Eyes (Víctor Erice)

There is never a moment in the enthralling span of Close Your Eyes that I have ever felt being shortchanged by Víctor Erice. Never has it crossed my mind that I am drawn to it only because his three previous films, the smallest but brightest constellation in the history of cinema, have affected my life deeply. Even at his most conventionally plot-driven, where there is a clear path being taken and an active character pursuing a goal, Erice treats the screen delicately, with depth and tenderness, not shying away from sentimentality. He won’t make you forget that fading to black is not merely a transition but a throbbing poetic device. He knows what he’s doing when he casts Ana Torrent, fifty years after The Spirit of the Beehive, and lets her say again, “Soy Ana.” He knows the ache we’d feel when his missing character is found but without a memory. He knows damn well that the setup of the movie theatre at the end will trigger the waterworks. “What would happen if he saw the footage from the last movie he made?” My fucking goodness. With Erice, whose kindness knows no bounds, there can never be a shortage of praise.

2. May December (Todd Haynes)

Come on, Norah’s Ark. That’s funny. Some moments you just have to laugh out loud. You’re not supposed to but you can’t help it. There’s a lot of nudging and winking, and it’s how you know that Todd Haynes is queering the material and elevating it. It is also sick. Elizabeth acting the shit out of that letter read, looking at the camera, arching her back. Elizabeth watching audition videos of toddlers to choose someone that will act opposite her. Elizabeth, in her Lydia Tár moment, responding to a question about shooting sex scenes. Elizabeth wanting another take. What I love most about Haynes is his reliability—he is never uninteresting. He is always serving. He knows how to arouse, and most arousing things are dirty. The nonfictional part of May December is enhanced immensely by the fiction, by the liberty taken to make the narrative more nuanced, more impressionistic. Imagine people on social media losing their shit over a film about. . . research?

3. Inside the Yellow Cocoon Shell (Phạm Thiên Ân)

As hypnotic as it is, there are no demons here. Inside the Yellow Cocoon Shell boasts an austere scale of simplicity, the way the finest Southeast Asian movies go farther in to look for answers, only to end up discovering something else, like how to be bodiless. Phạm Thiên Ân summons familiar phantoms. His pilgrim pulls the past and present with equal restraint, facing a tragedy with utmost calm as he finds his way in the highlands of Vietnam. One elderly woman tells him: “The brevity of suffering compared to eternity. . . is but a fleeting moment, barely anything.” Even the fog offers him wisdom.

4. Fallen Leaves (Aki Kaurismäki)

Oh, yes, the sweetest 81 minutes. I feel so much affection for this film. For its unwavering humour, for how it utilises rhythm and repetition, for how it re-presents cinematic time. “Epic” as an adjective, often misused blatantly, no longer means anything these days. But if I could reclaim the word I’d say Fallen Leaves is nothing short of epic. A narrative poem, an epyllion whose deadpan surface contains copious amounts of mirth. It is not cute or zany like most love stories try to be. There’s the developing news of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in the backdrop, but for some reason our foolish lovers have no smartphones. She writes her number on a piece of paper. He loses it. You notice these cool posters of films behind them. You chuckle a lot. What’s the opposite of larger than life? Kaurismäki is the master of that.

5. Mission: Impossible — Dead Reckoning Part One (Christopher McQuarrie)

Believe me, the more I follow this series the less I associate it with Tom Cruise. For instance, in this latest instalment, I think of the women and how they drift on the entire spectrum of incredible: Hayley Atwell, Rebecca Ferguson, Vanessa Kirby (two of her), Pom Klementieff. Fine, I also think of Simon Pegg screaming “my friends??!!” and how loudly I cackled. Dead Reckoning reminds me of early cinema—the Lumière Brothers, Keaton, Harold Lloyd. . . the dedication to delivering entertainment, to delighting audiences with action, to playing with a toy and that toy being a motion-picture camera. The prompts seem to be: How do we take it to another level? How do we make it more incredible? Questions that Méliès himself, anecdotally, had pondered many times.

6. Saint Omer (Alice Diop)

An unmistakably heavy film. I’ve thought a lot about where this heaviness comes from. The story, definitely. The parricide. The public trial. The dialogue and situations of the characters. But the heft also comes from Alice Diop’s filmmaking style. The burn. The precise cutting. The forthright framing. The length of each moment. The sense of drilling. I understand what’s going on and what has happened, but I’m also confused by how actions and arguments are being rationalised and defended. It strikes me how they comment on the immigrant’s “educated French.” Like how we speak a language determines our future and how others see us. How intellect and education are artificial totems we use only as protection from indignity.

7. Anatomy of a Fall (Justine Triet)

Anatomy of a Fall brings to mind Kieslowski’s Blue: the physicality of pain, the brutal ways that someone’s death can change your life, the commanding performance at the centre. But Justine Triet’s film is also obviously very different. It is not subtle. It does not steep itself in colour and its symbolism. What it does with such force, as though we were observing a speeding train and expecting it to crash, is perform a series of narrative manoeuvres. We see the railway tracks being switched, we hear the engine almost running out of fuel, we hold our breath. And the crash happens. The visualising of the audio recording, edited brilliantly, can only be compared to a panic attack that doesn’t stop. How Sandra Hüller has managed to come out of the wreck alive means that, like Juliette Binoche, she is superhuman.

8. R.M.N. (Cristian Mungiu)

Should every Cristian Mungiu film be upsetting? Do we need his films to hate the world more? His body of work is a perfect reminder of how much our society has fucked up and how it will keep fucking things up more. I could not have prepared myself for the intensity of rage and sullenness I felt after seeing R.M.N. There is a long, static shot in it that is similar to the harrowing scene in 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days—you will instantly make the connection once you see it—and the paralysis sets in quickly. It is constantly bleak. The sun never rises. Are you telling me that the xenophobia and racism are based on a real-life incident? The toxic masculinity, too? Shocker. Is this the Transylvania of Dracula’s time? Is it Dracula that the child saw?

9. Beau is Afraid (Ari Aster)

What’s the consensus on this? Thankfully there’s none. I’d say this is Ari Aster’s best work yet (the way Nope is Jordan Peele’s; fight me) and by “best” I mean most ambitious, funniest, messiest. Where he risks the most. Where he is most excessive and careless. Where I gasped and snorted so many times I had to cover my face on my way out of the theatre. Like Hereditary and Midsommar, Beau is Afraid is a simple story made complex by how it is told. I can’t help but cheer for the sheer audacity of the filmmaking, the kookiness of its signifiers, the mere presence of Patti LuPone and Parker Posey jolting everything. It is such a hilarious film. So much anxiety, restlessness, confusion, foolishness, rendered extremely. The film lets you breathe, but most of the time you forget that you are not breathing anymore. I agree: Ari is being a dick. What a dick. And what a dick ride.

10. Afire (Christian Petzold)

I often say that I prefer my films being facetious. I’m not here to tell you what constitutes this facetiousness, but it shouldn’t matter whether it’s intentional or not. Unlike Christian Petzold’s earlier films, Afire is not set during a particular war or immediately after it. This does not seem to matter much. It still feels like the people in it carry the burden of their time. The facetiousness comes from the Main Character—exactly how Film Twitter would describe him—a self-centred novelist finishing his second book. Leon is mean and narcissistic, which is why he is not having any of the juicy sex the others are having. (Fine, I’ll say it: his chubbiness makes him endearing. Glad for this representation, but he’s an airhead.) For a novelist, he can’t see the bigger picture, and this obliviousness has saved his life. Now isn’t that funny! Bisexuality, mysterious fires, Paula Beer reciting a poem twice, the iniquity of writerly pursuit—a nerd’s fever dream.

11. Barbie (Greta Gerwig)

I hear you. You hate it? It’s mid? It’s overrated? It’s woke? It’s corny? It’s not. . . uhm. . . believable? The plot is. . . what is that ugly word. . . meh? Why should we celebrate this pinnacle of liberal, pro-capitalist, white American feminism? I don’t know. I don’t have answers for you. But let me tell you, in America Ferrera’s voice: the female body disturbs the cinematic space like no other. It is the most fascinating source of commotion, on-screen and off-screen. I like a film that triggers an eclectic set of categories: conservatives, purists, incels, cinephiles, boomers, millennials, Gen Zs, people whose only identity is being cool. I also like it because it is brimming with ideas and references. I get the jokes. I get the artificiality. It’s made up of silly parts and the whole thing is profound. It’s a supermarket and I get a nice tote bag. It’s not a choice between taking Barbie seriously and not. The conundrum is where do you make the choice.

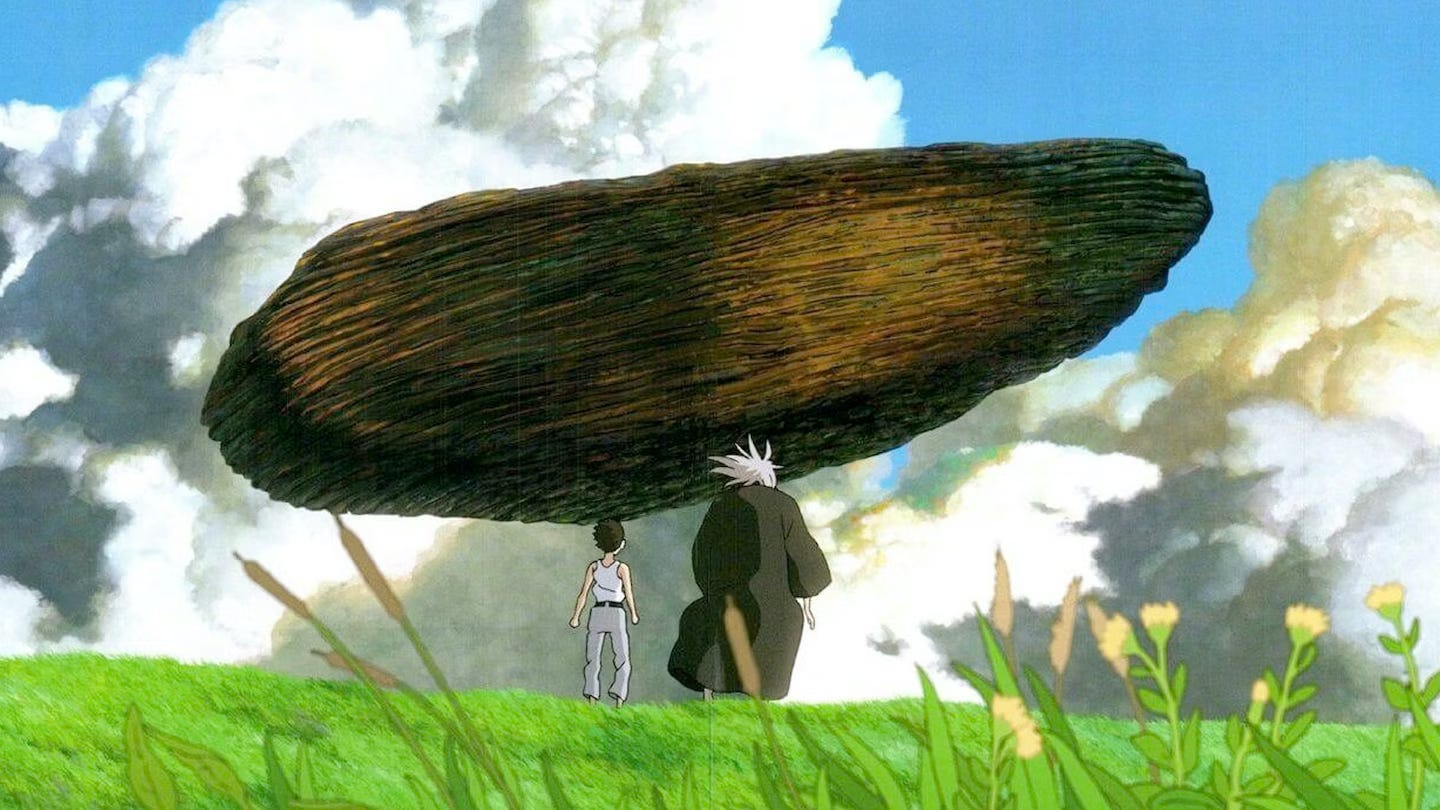

12. The Boy and the Heron (Hayao Miyazaki)

Sometimes, when I fancy going to great lengths to scare myself, I imagine our world bereft of Hayao Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli movies and I shudder at the massive void this means to our collective imagination. Their body of work has broadened and deepened the humanity of film, allowing us to recognise that the earth is not a cold, dead place and everywhere we turn there are portals where creatures are awaiting our entrance. As demonstrated skilfully in The Boy and the Heron, this world is dark and beautiful, and most things that happen to our lives do not follow any logic. The boy in the film loses his mother, and his grief makes him both powerful and powerless. Miyazaki never acts like a god—he himself does not understand how the universe works. He shows us that humans are but a tiny speck. There are parakeets, frogs, pelicans, herons, and the cutest warawara, whose journeys are as consequential. Birth and death are not the beginning and end. Our worth does not depend on knowing. In the vastness of the visuals and music, Miyazaki always measures the lives of his characters in how much they allow themselves to lose their way.

Petzold's great. Love that oafs finally got our moment in Afire

missed your writing, sir!! and love the brit-ification 🧡