“If You Look for a Meaning, You’ll Miss Everything that Happens”

On Cleaners (2019) written and directed by Glenn Barit

This essay is published in the booklet accompanying the Blu-ray release of Cleaners. Much love and thanks to Pearl Chan and Ariel Esteban Kayer of Kani Releasing for their passion for Philippine film (check out the other titles in their roster, including Minsa’y Isang Gamu-gamo, Kakabakaba Ka Ba?, and Cain at Abel) and for allowing me to reprint this essay here in full. In keeping with the spirit of Cleaners, Pearl wrote the whole piece by hand, and everything else in the booklet. Thanks also to Glenn for the conversations that have provided the shape and soul of this essay. You can buy your copy here. The Blu-ray is gorgeous and contains loads of stuff, which you can see in my Instagram post.

Filipino cinephiles are quite easy to spot because one of their old habits is they won’t shut up about their longing for a particular time. May it be the era of Lino Brocka or Ishmael Bernal, the flourishing decades of Star Cinema, or the loss of sorely missed haunts for film-related obsessions, Philippine cinema won’t ever die because it is being remembered constantly, unwaveringly. It is an industry forsaken by its people from time to time, cursed for good reason, but it is also a concept we love caressing, an integral part of ourselves and how we talk about our lives, how we think about our future. Film exists as a memory for the audiences that have lived through it. And it lives as a reality—the identity and inclination of which we are bound to accept no matter what shit cinema finds itself in. This means it can change us and we can change it. Within cinephilia, there is love and there is pushback, creating lodestones of longing steeped in time.

When Cleaners premiered at the QCinema International Film Festival in October 2019, the world was only a few months away from a decisive moment. Hardly anyone foresaw the magnitude of such a Gestalt shift. Hardly anyone worried about the end of a myth, a fable everyone in the industry knew and told, that invigorated us well for over a decade. 2019 was remarkable for its wealth of movies, and a rundown of titles from memory could be disorienting. Edward; John Denver Trending; Sila-Sila; A is for Agustin; For My Alien Friend; Isa Pa, With Feelings; No Data Plan; Ulan; Babae at Baril; Alone/Together; Kalel, 15; Kaaway sa Sulod; The Kingmaker; Dead Kids; Between Maybes; Jowable; Sunod; Verdict; Metamorphosis; Mindanao; Kuwaresma; Family History; Hello, Love, Goodbye; not to mention the cluster of superb short films and screenings of restored films in niche spaces across the country and on streaming platforms; film events that regularly took place if one knew where to look and who to ask. A similar argument could be made for the haul of the previous years, sure, but they did not have the bragging rights of directly preceding a pandemic. 2019 beguiled us, for an oblivious second, into believing that the offline and online experiences of cinema could be sorted out. That the cannibalizing did not have to be catastrophic. Eventually more curtains were drawn. The succession of luminaries passing, from people unreachable to us to those walking in our close circles—Eddie Garcia, Tony Mabesa, Luis Nepomuceno, Peque Gallaga, Joseph Laban, Eduardo Roy, Jr., Gloria Sevilla, Susan Roces, Cherie Gil, a constellation taken away abruptly—demonstrated that there’s a time to live and a time to die, happening necessarily in that order. Absence will always be deeper than presence. It’s the myth that will endure, and the myth having an ending makes it more potent to be idealized.

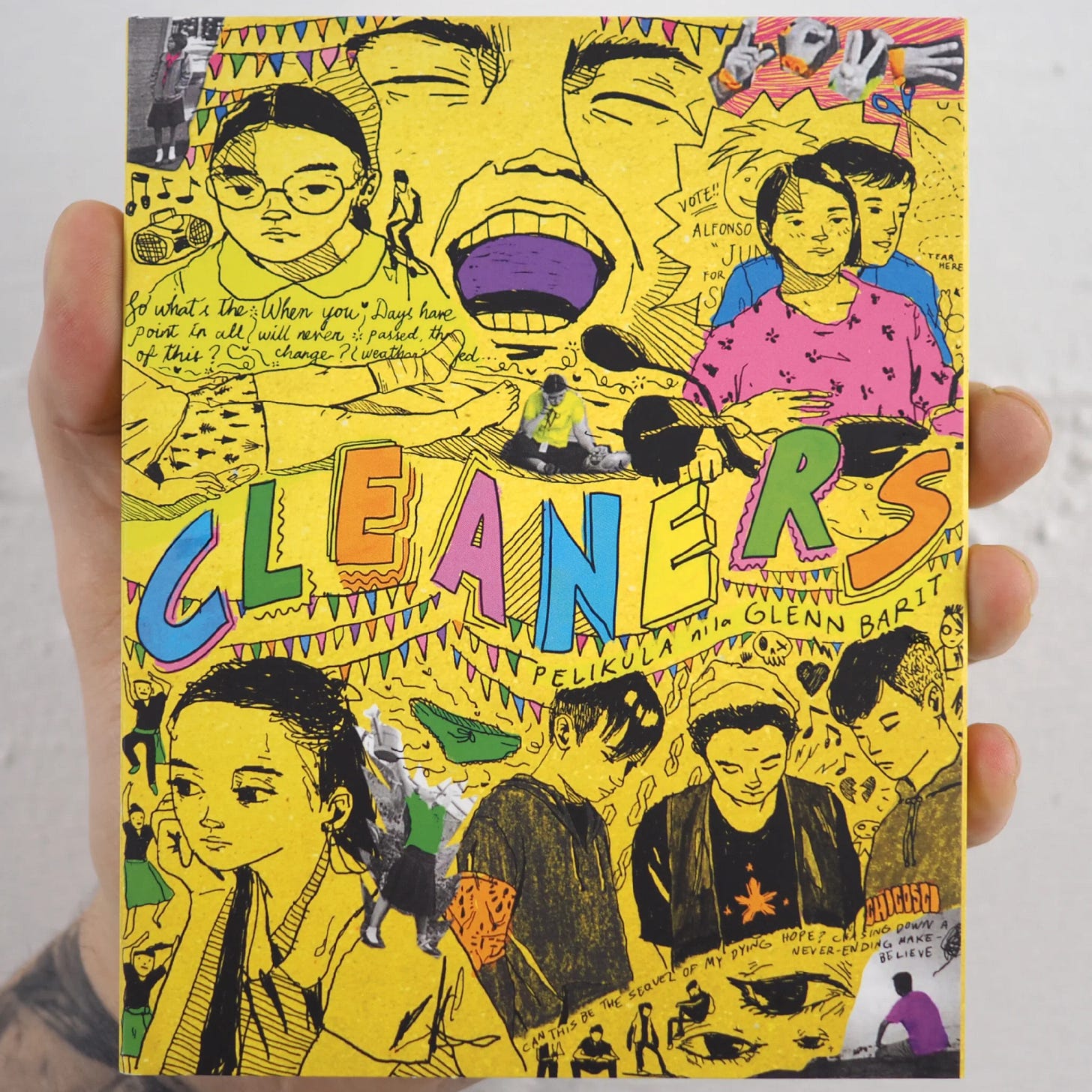

Ask Glenn Barit about this myth and he might wax sentimental. He is a writer, director, producer, cinematographer, sound designer, composer, actor; a multihyphenate out of sheer necessity and natural curiosity. In his work, instead of putting “a film by” he writes “pelikula nila/nina,” a literal translation affirming that, despite wearing many hats, he is not the author alone. From Bundok Chubibo (2014), Aliens Ata (2017) and Nangungupahan (2018) to Maski Papano (2020, with Che Tagyamon), Walang Katapusang Hurno (2021), and Luzonensis Osteoporosis (2022), his short films possess the quirks of youth, meaning they are charming and funny, playful and sincere, intuitive and dreamful, altogether esculent enough to be swallowed in one go. He tells legible stories of love that convey hurt and melancholy, relationships eroded by the passage of time, lives being lived. He likes tricks and harnesses a style that refuses the sleek and glossy, a process that foregrounds materiality, a voice that shifts between a child and an adult. His imagination, growing as each picture gets made, has long been wanting a bigger canvas, and all roads lead inevitably to his first feature. A moving-up ceremony, as we’d like to call it in the Philippines.

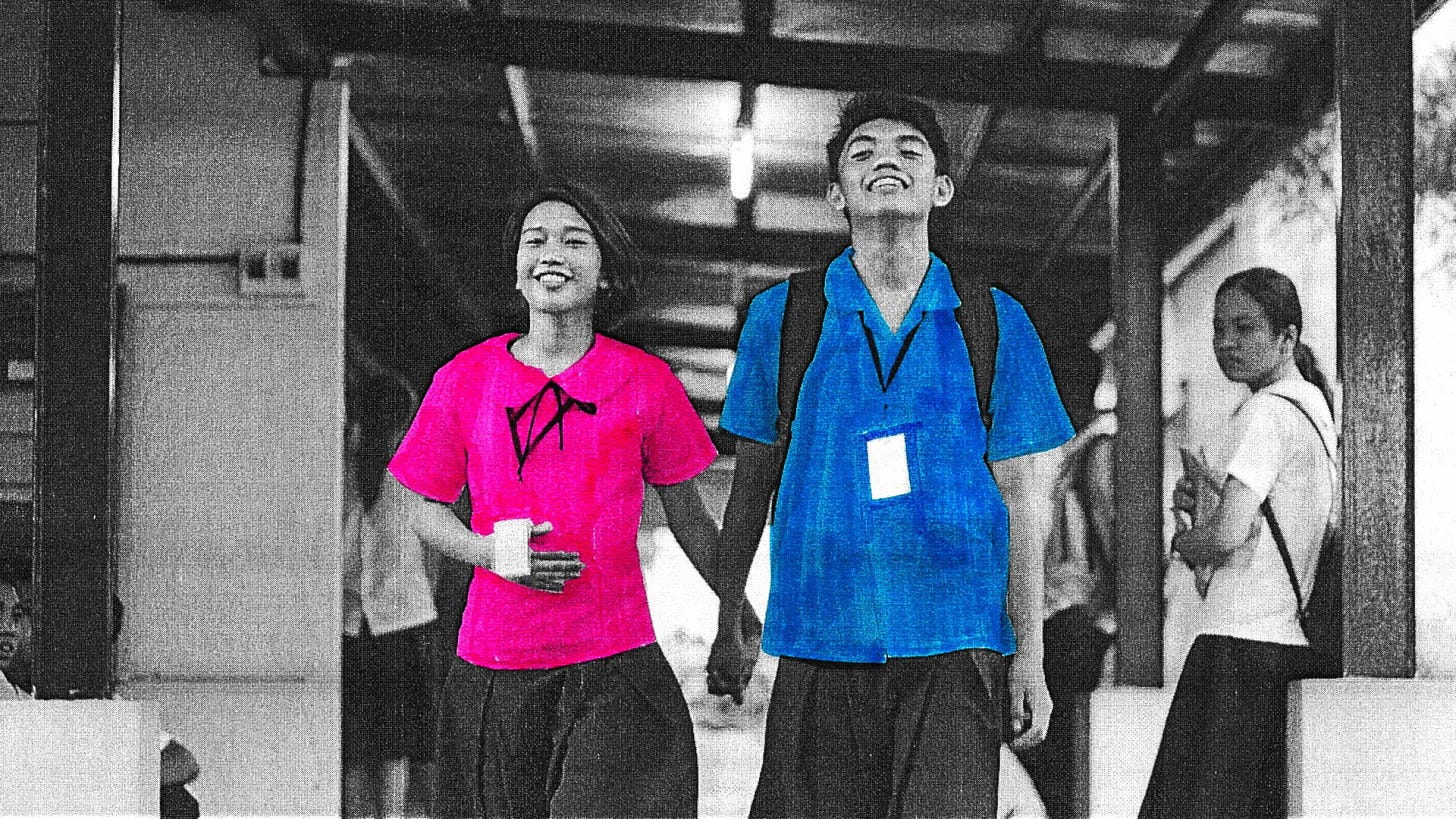

Cleaners is this canvas. A novel experiment of lasting beauty, Cleaners is not only a highlight of his career (pun intended) but also one of the brightest spots of contemporary Philippine film. Barit himself has been longing for a particular place and time, specifically the city of Tuguegarao in Cagayan in 2007, more specifically his time at the University of Saint Louis Tuguegarao as a high schooler being infatuated with emo culture and discovering emotions new to him, being forced to conform and rebelling against it. The desire to immortalize one’s hometown in film is not unusual—think of Greta Gerwig’s Sacramento or François Truffaut’s Paris or Mes de Guzman’s Nueva Vizcaya1 — but in Barit’s case it is special because Cleaners is the first feature to be shot entirely in Cagayan and to boast an ensemble of nonprofessional actors from its communities. It comes from a sense of pride, like a teenager wanting his friends to see his room and play his new videogames—a teenager like Barit. The film’s use of place, however, resists the parameters often ascribed to “regional cinema” that tend to exoticize the provincial and treat the audience as visitors, touring them around the sights and offering the delicacies. If anything, Cleaners speaks about the familiar: whether the formative experiences of first love or companionship, the recognizable lot of characters in one’s purview (friends, enemies, and bystanders at school or in any social environment), or the spirit that lends a hand in times of extreme need. This familiarity gives it a modest, unpretentious quality. There’s a smallness to it that makes it easy to hold, a bite-size confection rolling in one’s palm. It is broad and specific. It tells your story but not exactly your story. It tells a joke you might not find funny but others definitely will. It’s not about you and it’s also about you.

Of course, the smallness is a ploy to make the big issues apparent, in the same way that the familiarity makes the unfamiliar stand out. To an audience who knows nothing about the Philippine school system, the idea of student cleaners might come across as a quirky device for a dramatic multi-character narrative, but it is in fact a common fixture of our primary and secondary education, accepted without question, integrated into our understanding of independence and servitude. Plastered on the classroom walls and etched in our collective memory is “Cleanliness is next to godliness.” We are strangers put together in groups, being taught the values of obedience. Whoever is hired to clean the rooms and the building premises, if there is one, cannot do everything by themselves—the pay is peanuts for such a backbreaking job—so it is only rational that we, the students who use these spaces, tidy up after the day, one team after another, week after week. Should we dare make a sweeping argument out of this, the massive number of Filipino domestic helpers exported to almost every country across the world has its roots in this responsibility as a young student: scrubbing the floor, dusting surfaces, wiping the chalkboard. Taught to serve and sacrifice, they also think of freedom at the end of a long day.

The proximity of Cagayan to Ilocos Norte, the hometown of the dictator Ferdinand Marcos and his son, the current president of the country, is underscored in Junjun’s story. Junjun himself is being groomed by his parents to continue their political dynasty, a foothold that sharpens the film’s sense of place and time. Where we are, to which family we are born, determines what we can be. We can fight or escape it, but there are larger forces at play. When do we start believing what we believe in? How are our political values formed? Cleaners treads on these questions and moves in almost the same space as Lav Diaz’s Norte: The End of History (2013), particularly with how it engages the milieu’s geopolitics and examines the implications of proximity. Marcos Sr.’s economic and labor policies in the 1980s catalyzed the large-scale movement of Filipinos abroad, many of whom were forced to leave their families behind. The dissolution of the Filipino family is one of his regime’s horrible legacies. Marcos Jr.’s role, decades later, is to clean his family’s reputation, to regain control of the political narrative and replace historical facts with blatant lies. In both these films, it is clear that it is no longer enough to simply acknowledge that everything is political. We must point fingers and speak their names.

Junjun’s story is not just a political family’s tale or a boy’s discovery of corruption—it’s our story as a people, too. Its placement at the end does not mean that it holds the segments together, or that his story is more consequential than the others, but it ostensibly carries the large and largely depressing sentiment of the film. Junjun can be seen everywhere, harmless, conscientious, helpful. He observes his parents laugh maniacally and follows their example, opening his mouth as wide, thinking it is what he should do. Barit does not apologize for him, or for what he represents. He inserts a humanistic picture of him contemplating at the end of an unfinished bridge, a piece of infrastructure on which his future depends, recalling the Marcoses’ “edifice complex.”2 It makes sense that it is Junjun who initiates the screaming in the coda, for he is the first of the gang to die, so to speak, the first to say fuck you all before his innocence withers. There is no turning back.

High school is a crucial time when our concepts of the world are constantly being challenged. Drilled into our heads, for example, is the notion that a tidy appearance equates with the integrity of spirit. To be morally upright is to follow the scriptures and resist temptations. School defines for us the good and evil, but it is only a placebo that barely protects us from anything. School is a rough place oblivious to its own violence. In Cleaners, we see a teacher reprimand Stephanie for not taking care of her seedlings. We see a teacher cut the boys’ hair and confiscate their music CDs because they do not abide by the school’s regulations. We see a teacher wince upon hearing the emo music used in a traditional dance presentation. We see a teacher talk to Britney’s parents about the decision to expel her from school because of her pregnancy. These teachers may know more about the world, but they obviously do not know better. They do not see, or they refuse to see, the bigger picture: the trauma, the bullying, the micro- and macro-aggressions, the skirmish leading to irreparable damage. There is a divide between the teachers and the students who interact only in terms of compliance. They never really see each other eye to eye. Barit shows the cracks of these conservative values and hypocrisies through a biting sense of humor and puts his characters in situations that compel them to fight back and take control of their lives. Students survive school, literally, by coming out of it alive, laughing at their luck and misfortunes.

It is impossible to read a review of Cleaners that does not trumpet its visual style—rightfully so—but in so doing its simplicity is sometimes regarded as a shortcoming, an inferior quality attributed to the tone of coming-of-age movies, to the worldview of adolescents. But this insistence on a simple narrative design is the reason that it reaches such great depths emotionally. Barit prefers a coherent turn of events and makes straightforward choices. Characters are introduced episodically, each or collectively given a specific color to make them easy to follow. The seedling grows because of the shit it is given. The parents teach their son their corrupt ways. The pair of scissors has a remarkable plant and payoff, utilized in the film’s most shocking display of simplicity. The emo boys believe in a chain message saying their friend is dead, and their reactions are visualized succinctly like a comic strip. The humor also depends heavily on the candidness of the music and its cues, on the amplitudes and textures of sound, that, on one hand, pay tribute to Barit’s inspirations and, on the other, acknowledge our lives as a palimpsest of follies, a tapestry of melodies.

Whenever I think about the film’s pictography, I get stuck in this plain, corny, but nonetheless fitting analogy: The journey of a bicycle will always be different from the journey of a car. The cyclist takes longer, exerts more effort, and tells you more colorful anecdotes from the road. The views from a bicycle tell a different story, imparts a different experience. Especially if you think about cycling in Metro Manila: full of hazards and, if you survive it, pleasures. Specifically: how does a film consisting of 8 frames per second, with over 30,000 printed and photocopied images, selectively colored frame by frame using fluorescent highlighters and eventually scanned and assembled in the final edit, get made in this age? Why strive for this visuality? Why take this route? On his crowdfunding website, Barit cites two reasons3. First, it reinforces the film’s theme of cleanliness and perfection (“The unpredictability of the photocopier hopefully disrupts [the glossiness of high-resolution digital filmmaking]. We want the stain of the ink and the ‘mistakes’ from the [clunkiness] of the old machine to dictate the look of the film.”). Second, it accentuates the setting through the use of school materials, e.g., paper, ink, markers, Xerox machines, etc. (“You will see all the strokes from each highlighter [on] the big screen.”), thereby foregrounding the labor involved in the creation.

This kind of rebelliousness in a reactionary industry usually sets one up for rejection. After receiving a no from one grant-giving body, Barit submitted the script for funding to QCinema, whose 2017 edition opened with Loving Vincent (2017), the fully painted animation directed by Dorota Kobiela and Hugh Welchman about the Dutch painter whose gorgeous, lifelike textures inspired Barit to develop the aesthetics of Cleaners. Another influence was A Trip to the Moon (1902), particularly how George Méliès and his team painted colors directly on the film stock. The approach piqued the interest of the QCinema selection committee, who loved his script but expressed hesitations about his plans. The material is good, but couldn’t he shoot it conventionally? With the labor needed to fulfill his vision, could he finish it in six months? Won’t it be too much if the whole thing looks like that? What if the gimmick becomes tiresome? Would he consider doing his chosen treatment in just the climactic scene? Barit replied tersely: The treatment is the very point of making the film. It was the three-million-peso answer that made the doubts worth seeing through.

The longing to bring back to life the Tuguegarao of his high school days also required Barit to bring back his own juvenile spirit from 2007. Cleaners is a document of disavowal as much as it is a display of its storyteller’s defiance. Barit’s critique of the shiny, polished film surface being treated as the aesthetic default recalls the German filmmaker Hito Steyerl’s articulation and defense of the poor image, in which she perceives the dominance of sharp, high-resolution images in art and media and the reverence ascribed to them as a function of neoliberal corporatism4. This results in the association of the so-called poor image, itself a product of history and political economy, with the substandard and the illicit. We are conditioned to equate quality with clarity, virtue with cleanliness. Seeing grain makes audiences uncomfortable. Netflix and streaming culture dictate this. The proliferation of motion smoothing on television screens contributes to this. Even an industry that purportedly champions independent filmmaking is susceptible to rejecting the poor image of the abstract and experimental film and its politics, an attitude, according to Steyerl, that “is not only connected to the neoliberal restructuring of media production and technology; it also has to do with post-socialist and postcolonial structuring of nation states, their cultures, and their archives.”

The emphasis on the bespoke production of images and their assembly is fascinating, almost heroic, because the result forces us to look at the screen with a different pair of eyes, with our sensibilities conditioned to appreciating only crisp images and seamlessness slowly becoming attuned to imperfections, to a reality often obscured. Cinema allows both obedience and rebellion. For a process that relies on cycles of reproduction, it’s also marvelous to call the result original. If the goal is to make Cleaners look like “a handmade high school project” it succeeds, and also achieves more. Each stroke of the highlighter has a unique texture, filling in the space but also going over it sometimes, coarse and rugged, real—as though saying these are not AI processors but actual tired hands, a small team, pulling an all-nighter, driven by a dream and a deadline. The explosion of colors in the climax as the characters scream and trash the classroom, accompanied perfectly by Unique Salonga’s soulful voice, is as moving as any cathartic release in a movie, coming-of-age or not. Sublimely human; a profound feeling that no technology could have ever generated.

What is being longed for here? Perhaps, in this age of shameless commercialism, in this era where everything is regarded as metrics, as we are trapped in a pessimism growing exponentially post-pandemic, perhaps the one thing that can keep us afloat is humor. The kind of humor that allows us to live. The kind of humor that is human. Two older colleagues of mine who did not like the film echoed a similar sentiment: What’s so funny about a fart joke? Why should we laugh at someone who shits herself in public? Why do we have to see a bloody foreskin being thrown at one’s face? What came to mind was the famous Tarkovsky quote, one word of which I often found myself giving a different inflection: “If you look for a meaning, you’ll miss everything that happens.” But instead I said something simpler and truer, spoken like a child brandishing his first curse word: It’s fucking funny. It just is.

Notes

1 Specifically: Lady Bird (2017), Les quatre cents coups (1959), Ang daan patungong kalimugtong (2005).

2 See Gerard Lico, Edifice Complex: Power, Myth, and Marcos State Architecture, Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press, 2003.

3 “Cleaners Film: Help fund our nostalgic highschool Tuguegarao” https://fund.thesparkproject.com/project/cleaners-film-fund-our-photocopy-and-highlighter-look (Accessed: 01 August 2023).

4 Hito Seyerl, “In Defense of the Poor Image,” e-flux journal #10, November 2009.